On Risk, Incident Response, and Coronavirus

08 Mar 2020If you want to skip to the goods, click here. If you want to skip straight to the purely professional content, click here.

Foreword

It’s been a while since I spent time writing for personal gratification. My personal and professional journey has lead me pretty far from analyzing exploit kits on a day to day basis. I’ve spent the last three and a half years building out and leading GitHub’s Security Incident Response Team (SIRT) and the processes that guide it. I’ve had an opportunity to take the foundation of how we work laid out by those that came before me, frame it out with scalable and compliant process that fits GitHub’s remote-first, asynchronous-by-default culture, and accelerate it through massive company growth and acquisition by Microsoft. I was something like employee number 310 (not accounting for churn, of course); we’re now over four times that size and still accelerating with an ever growing and awesome platform and product portfolio I’m proud to help protect. I’d be remiss, however, if I didn’t take an opportunity to thank the amazing professionals I’m lucky enough to call peers and teammates, GitHub SIRT would be nothing without their dedication, their creativity, their camaraderie, and their tireless excellence.

With that out of the way, on to the purpose of this post: thinking about risk management and incident response as framed by current events, namely the novel coronavirus officially known as COVID-19. Before we get to the good stuff, a brief disclaimer:

Though this post discusses coronavirus, this is simply a way to frame thinking about the disciplines of risk management and incident response. None of the statements that follow should be interpreted as authoritative guidance on coronavirus or disaster preparedness and all of it is subject to my personal opinion and admitted lack of expertise regarding anything like epidemiology or traditional emergency management. If you’re looking for formal, sanctioned advice, seek out the World Health Organization, US Centers for Disease Control, or your local health authorities. I say again, do not take my personal opinions on and preparations for COVID-19 as professional advice.

Further, my professional background is much more about threat and risk mitigation than forecasting and quantification. There is a formal discipline associated with risk that I have limited formal training in; as such, I tend to simplify risk into a basic framework that allows me to make informed decisions. I have found it effective throughout my life and career, but I have no doubt it could be done more scientifically or more comprehensively.

Coronavirus - A Primer and Personal Approach

Unless you’re living under a rock or in some sort of news-vacuum (ignorant bliss?), you’re well aware by now of the rapid spread of coronavirus, officially known as COVID-19. Believed to have originated in Hubei Province, China, this is a new strain (hence the term novel coronavirus) of a class of cross-species viruses capable of infecting humans. In many humans, the disease appears to be mild, but in some percentage of cases, particularly among the elderly or those with underlying conditions, victims can develop severe and even fatal respiratory complications. Though it’s early and a lot more study is required, COVID-19 appears to spread more readily than the flu and carry a higher (but not outrageous) mortality rate than the seasonal flu.

In terms of perspective and forming the basis of a risk picture, the seasonal flu has sickened between 34 and 49 million individuals this season. The death toll for seasonal flu in 2019-2020 stands somewhere between 20,000 and 52,000 (¹). COVID-19, on the other hand, since its known emergence in late December 2019 and at time of writing on March 8, 2020, has resulted in 109,965 clinically confirmed cases and 3,824 deaths (²). It’s important to understand, that despite these much lower numbers, there’s a substantial amount of uncertainty due to the mild presentation of many cases and the low availability of test kits worldwide. That said, you’re still far more likely to be affected by the seasonal flu than you are COVID-19 unless you happen to reside in a viral hotspot where the disease is more prevalent. That’s about as much explanation as I’m going to give because I’m not really qualified to give it; see the disclaimer above for more authoritative info.

With a basic understanding of COVID-19 established, I want to share some of my personal perspective on the virus and my family’s risk assessment and preparation for it. Below, I’m going to outline some of my thought process, the resulting “threat model” we used, and the preparation we undertook to meet that threat based on our personal situation. All of this has parallels to security risk management and incident response and I’ll discuss that following this section.

Situational Awareness

The first, and perhaps the most important thing I focused on was maintaining well-informed situational awareness, right from the get-go. While I do not consider myself remotely paranoid and I am fortunate enough not to suffer hypochondria in this particular case, I do keep my head on a swivel at a global scale for both personal and professional reasons. Perhaps a decade of security, risk, and intelligence work is the reason for this, but I was sort of loosely tracking this coronavirus outbreak as early as the first two weeks of January.

It wasn’t a focus, I didn’t dwell on it all day, but I did watch closely enough to be able to begin building a mental model for the risk it represented to me, my organization, and to daily life. I paid attention less to the specifics of the outbreak than the shape, size, and velocity of it. This feeds a sort of equation in my head that is constantly re-computing based on the new input I gather daily, for lack of better terms. While there is a formal scientific discipline dedicated to this work, I’m not trained for it, so my internal calculation is intentionally vague and elementary in nature. The point is simply to be able to track the overall trend represented by developments related to coronavirus and how the basic risk I assign any event or circumstance, in this case COVID-19, is growing or changing. Understanding this, even within my own mental framework, is the basis of how I make informed decisions with risk in mind.

It is absolutely vital that you maintain situational awareness at all times. Failure to identify and assess a risk in the first place leaves you unable to prepare, rendering your ability to level the playing field as much as circumstances permit essentially null.

Building a Basic Mental Model of The Problem

My next step is to begin developing mental models around the problem and its possible manifestations. In the case of COVID-19, I began thinking about some plausible long-term outcomes. Those outcomes roughly looked as follows and are oversimplified, discounting a whole lot of good epidemiological science about things like R0 and mortality rates among other things:

- Virus is largely contained by aggressive response in China and fizzles as the warm season approaches, remaining only an isolated and periodic threat relegated to dozens or fewer easily isolated cases per year.

- Virus is not contained, but does not readily spread. Slowed by control and isolation efforts, it does spread globally or regionally, but is limited to local clusters and eventually snuffed out before the following flu season.

- Virus is not contained and spreads rapidly in an increasingly interconnected world. Governments in free societies or underdeveloped nations struggle to contain local clusters and rapid community transmission occurs. Seasonal impact is high, akin to other modern seasonal flu epidemics (see 2009 or 1957-1958) but eventually slows to a crawl and peters out, representing no threat greater than a moderate flu pandemic.

- Virus is not contained, spreads rapidly and with limited impact from control and isolation efforts. Virus develops a rather severe mortality rate and has a major global impact, presenting a substantial risk to health and way of life for one or more years. An example might be the flu pandemic of 1918.

Keep in mind that these models aren’t set in concrete and they change as time goes on and things change on the ground; I’m constantly re-calculating them. These models shouldn’t be static and should adjust to the reality you face. On a personal level, I suspect we’re looking at either the third or fourth model at this point. Much remains to be seen, but those models are the basis upon which I am operating today.

Develop a More Nuanced “Threat Model”

Now that I understood the basic shape of the problem, I wanted to think more concretely about what the actual threat looks like. My wife and I discussed (and continue to discuss) our mental threat model and this is the set of things we selected as threats, based on our home and life situation:

- Possibility of voluntary or mandatory at-home-isolation for as long as a month due to local outbreak

- Possibility of temporary (lasting a month or two at maximum) supply shortages of items like food, medicine, paper products, and cleaning supplies

- Increased risk related to public gatherings or travel via public transit

- Possibility of caring for one or more sick and contagious persons at home with limited external assistance

Things we decided to exclude from our model based on available evidence:

- Water shortages or water quality problems (some preppers out there are probably incensed at this decision)

- Utility outages

- Large-scale societal breakdown or zombie apocalypse

Identify your Assets and Vulnerabilities

The next step for us was asset identification. We wanted to think deliberately about what we needed to protect and any special considerations that affected those things. We identified the following critical assets, all living things due to the nature of the problem:

- Two adults

- Two school-age children, the most important assets we have to protect (talking about your children as assets is admittedly uncomfortable)

- One indoor cat

With the basic assets identified, we set out to think about the things needed to keep them happy and healthy, with an eye toward identifying vulnerabilities or gaps that might increase our risk if unaddressed:

- One of the adults in our home has substantial underlying conditions that may place them at increased risk for infection and subsequent complications

- One adult has a significant dietary restriction which requires low fat consumption

- Both children are in public school, which represents a substantial vector for transmission

- We don’t keep deep stockpiles of most things, we’re prepared for brief life interruptions, but nothing beyond a week or ten days

Prioritize and Prepare

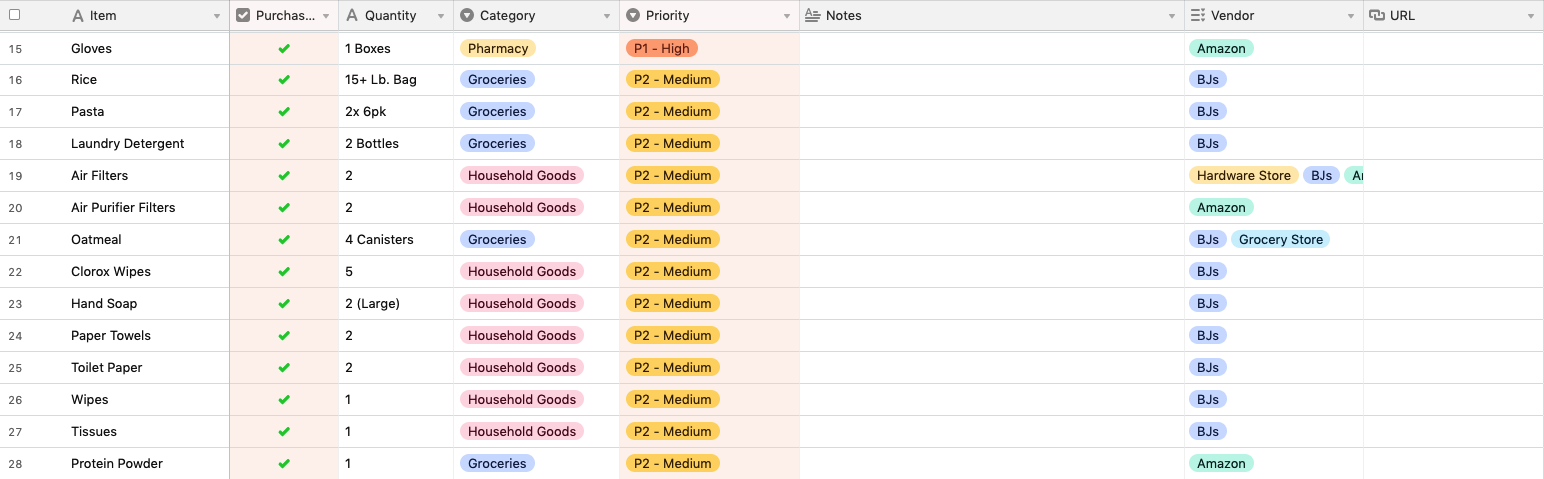

Incident response, whether it be related to an epidemic or otherwise, is all about effectively mitigating as much of the risk represented by that incident as possible. In order to do this effectively, you need to be prepared before the incident begins. Regarding COVID-19, this meant that once we developed situational awareness and took stock of our threats, assets, and vulnerabilities, we needed to begin preemptively addressing those things. We began by collecting information related to epidemic and disaster preparedness from sources such as the CDC, FEMA, WHO, and others. We developed a simplistic spreadsheet of items we needed to stockpile as well as a to-do list.

Once we had a basic list, we began prioritizing that list based on our own ground-truth surfaced via the threat, asset, and vulnerability analysis we already completed. For instance, we know we have an adult with underlying conditions, we therefore assume the likelihood we will need to self-isolate is higher than the population at large and that we’ll need to do so sooner. Therefore, we accelerated our purchasing of absolutely essential items like food and critical prescriptions a number of weeks ago.

We also know that with two public-school age children, we’d need to be more aggressive than the average household in disinfecting and personal hygiene, particularly in light of the health conditions of one of the adults. Therefore, we prioritized cleaning supplies, hand soap, and hand sanitizer early on and bought them in responsible quantities before any sort of public panic set in.

Many of you are probably wondering about masks, particularly N95 masks. We deprioritized them aggressively because they’re difficult to fit, wear, and dispose of properly, making the effectiveness substantially lower for non-medical professionals. Further, masks really need to be preserved for medical and emergency response personnel as much as possible. All that said, because of the vulnerable adult in our home, we did purchase a small quantity, primarily to be worn by someone who is already ill inside the home. The intent is not to wear these in public day to day in a futile effort to reduce daily exposure, but instead to lower the risk of in-home transmission if, and only if, someone becomes ill while we’re isolated.

We also took care to prioritize some things people don’t generally think of until it’s too late because we took the time to look at our threats, assets, and vulnerabilities. Extra cat food and cat litter are perfect examples, as were our food purchasing choices; whereas many tend to stockpile comforting foods high in fat, we needed to make different choices based on our health situation. Instead, we’re stockpiled with lower-fat choices like beans and lean meats like chicken breast. Further, with a couple of young children, we made some deliberate choices designed to keep spirits up in tough times. We prioritized some fun snacks and silly foods that will add variety and spark joy during a monotonous isolation should one come to pass.

A final note on stockpiling and disaster preparedness: these things live on a spectrum and some folks have a very different personal risk calculation. We took a fairly lightweight approach to our preparedness. If full societal breakdown was part of our threat model, we’d be having a very different conversation that would drastically affect our day to day lives just to prepare. In our case, we basically deepened our stockpiles of things we already use every day. None of what we purchased will go to waste or burn a hole in our pocket if COVID-19 fizzles out.

While I’m hopeful COVID-19 fizzles out as the warm months approach, I now feel much more confident when faced with the possibility it will instead disrupt our lives in a significant way.

Thinking about Risk

Preparation for COVID-19 is nice, but why does any of that matter if you’re here to read about security? The answer is simple: the basic framework I applied to assess and prepare for the risk represented by COVID-19 is the same one I apply at work every day and there are lessons to be learned and reinforced from that experience that can be useful in our day-to-day professional lives.

The process I use boils down to the following:

- Keep your head on a swivel, never stop consuming data about potential problems. Identify and track potential problems early and often. Calculate and constantly re-calculate a basic trend for any potential problem - understand if it’s becoming more prevalent or impactful so you can begin preparations before it’s too late.

- When a given problem becomes relevant enough to begin preparing for, build a simplistic model of the problem and its potential outcomes, even if only in your head.

- Identify the threats posed by that problem, the assets you need to protect, and the vulnerabilities or gaps you have surrounding those assets.

- Prioritize and prepare based on a combination of the possible outcomes, the threat model you built, and the ground-truth regarding your assets and vulnerabilities.

- Though I didn’t cover this above, documentation is the final step in my process. Where time allows, you should not allow all the hard work in steps one through four go to waste. If the risk fizzles out, you have fantastic prior art to reference should it reappear later.

Some additional points to keep in mind when thinking about risk:

Paranoia is unhealthy, we have lives to live and businesses to run.

Awareness of and preparation for risk does not mean that you stop the presses, hole up in your home, or stop your organization from doing business in order to avoid a risk. As security professionals, we’re in the business of mitigating or preventing risk as much as possible, not eliminating it. Do not let preparation affect your organization’s goals and success; instead, protect and enhance the success of your organization by insulating it from risk with careful preparation that does not inhibit progress.

Your preparation should never harm others - or your business.

An extension of the point above, risk preparedness should never be completed at the expense of others. In our personal lives this means responsible supply purchases well before panic buying sets in. It means not panic-buying all the hand sanitizer or masks, which you’ll never use, at the expense of other families or medical professionals. In our professions, this means that we don’t require absurd and expensive risk reduction measures in the name of security alone. We instead take a balanced approach to risk preparedness and reduction with our productivity and efficiency in mind.

Track problems early and often, even if you can’t or shouldn’t act on them now.

If you make a regular habit of identifying and trending various problems, you will be infinitely better situated to prepare for and respond to them if circumstances require. In our COVID-19 case, this meant that I was preparing in February and way ahead of the game here in the United States; I wasn’t subject to supply shortages or the panic buying now taking place. At work, this means that we’re planning and prioritizing day to day work with possible problems in mind on an ongoing basis. Where possible, we rely on an inventory of possible risks to better inform resourcing and technical decisions every day instead of blindly checking checkboxes from some compliance checklist.

In short, risk awareness and preparation are really the name of the game. Bad things happen - that’s why incident response professionals exist after all. If you’re already aware of those bad things, know how they might manifest, and have completed reasonable preparations, you’re going to be able to respond and mitigate the risk much more effectively.

Incident Response and Communication for Incident Coordinators

You’ve been minding the shop and you’ve successfully identified and prepared for a given risk, but now it’s on your doorstep and you’re forced to respond - what happens now? I won’t be discussing incident response in depth here, but I do want to highlight some critical items that are particularly important for incident coordinators specifically - and relevant to current events.

If you actually have prepared, the first step is the easiest: have an effective incident response process in place. This should be well documented, it should define all the inputs and outputs of the process in accordance with your organization’s needs or compliance and regulatory obligations, and it should clearly delineate all the major IR stakeholders and their responsibilities. Most importantly, it should be easy to digest, easy to operate, and readily repeatable for any kind of crisis. Have this figured out before you’re facing that crisis. If you don’t, you’ll lose valuable time during the event and lost time usually results in more risk.

During an incident, as incident coordinator, it is your responsibility - your duty - to set the tone and lead from the front. Responders, whether security professionals or otherwise, rely on the incident coordinator for their example. If you panic, the rest of the team will likely do so as well; if - instead - you respond with calm and confidence, chances are you’ll make everyone in the room a more effective responder.

This doesn’t mean you make decisions in a vacuum or act like a tyrant. You’re neither omniscient nor omnipotent. If you make decisions without care and consideration and fail to collaborate with the talented professionals that make up your response team, you’re adding substantially to the risk incurred and it’s possible you’ll accidentally pour gasoline on the figurative dumpster fire. You should seek to make decisions by consensus and make those decisions guided by data as often as possible. That said, sometimes you may have to break a tie in deliberations or rely on your experience or even your gut to make a tricky decision. This is where it’s critical to set the course confidently, document your decision making reasoning, and orient the team to that course.

In terms of coming to those decisions, it is critical that action must be swift and decisive. Inaction is the enemy, whether by lack of preparation or analysis paralysis. Inaction delays mitigation, demoralizes responders, increases the risk incurred by the incident, and makes loss of victim or public goodwill more likely in the event that the incident goes public. As incident coordinator, keep the response tempo up and ensure the bias is toward action. Do not act rashly at the cost of analysis or consensus, but ensure that efforts to develop those things are always moving forward with clear deliverables and timelines established and understood by all responders. If things get stuck, it is important to call this out and either immediately clear the roadblocks or carefully make a decision to move ahead with the best information available - this is where past experience or your gut sometimes play a part. That leap of faith can be a nerve-wracking and imposter-syndrome inducing situation, but be confident in your skills and experience and let them light the way forward for you.

Once a direction has been established, no matter what part of the incident response process you’re in, that direction must be communicated unequivocally and with perfect clarity. No one in the room should be unaware of or uncertain as to the current course of action and their own responsibilities. If they are, for some reason, that course of action and those responsibilities should be quickly, easily, and clearly discoverable. Keeping status summaries and responsibility assignments up to date in a well-known and accessible location is critical and should be a top priority for the incident coordinator. Nothing will feed chaos and increase risk more than a room full of people without clear direction and assignments running in different directions and working at cross purposes.

Finally, extend these principles, particularly regarding clear, decisive communication when informing customers or the public. If clear and decisive communication are critical inside a room full of professionals, imagine how important they are for an uninformed or unprepared public or customer audience. All of your communications with external parties should make it very clear, in plain english, what happened, how it affects them, what you’re doing to respond, what they can do to help themselves, and where they can get help. Delivering anything less only compounds the incident by causing confusion, inciting concern or panic, and adding work for responders that get tied up in responding to a million questions and clarifications.

Incident response is a broad discipline and circumstances can vary wildly from event to event, but I’ve generally found that the principles above can and should be applied at all times. These aren’t specific technical to-do list items; they’re a philosophical approach for clear incident response coordination, leadership, and risk mitigation. These things make any incident coordinator, in any situation, a more effective force multiplier for a capable and prepared incident response team, which is the crux of the role.

A Call to Action - For Incident Responders, Public Health Professionals, and Emergency Management Leaders Alike

Too often, I see, hear, or read about incident responders wrapped up in the technical nuts and bolts of their professions. In the case of COVID-19, I see a lot of discussion about the technical intricacies of R0(the reproductive factor of the virus, or how easily it spreads from one host to others) or the mortality rate in clinical environments. In the security profession, it’s endless presentations and blog posts about the specifics of a hot new exploit or analysis technique. To be clear, these things matter immensely and have their place in our professions, but it’s vital not to focus on these things at the expense of some of the fundamentals, particularly in the role of incident coordinator.

To those working in incident response, or emergency management, I’d encourage you to buckle down on your risk management practices, your leadership and decisiveness, and your communication. These last few weeks, various governments and health agencies across the globe have been criticized for poor preparation, slow decision making and dissemination of those decisions, poor decisions made with incomplete data, and public messaging as clear as mud.

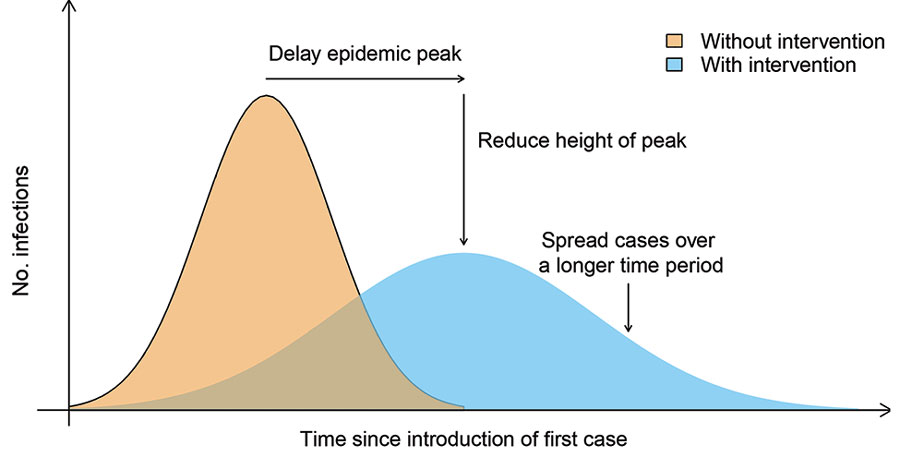

These things matter. Response time and effectiveness is risk. If we’re slow and perform poorly, risk increases. If we’re decisive and effective, it declines. In responding to epidemics, this is especially so (³):

While we can’t prevent the likes of COVID-19 or the security incidents we’re responsible for entirely, we can be better prepared and respond more effectively. If you do nothing else, prepare yourself, your organization, or the public on a constant basis, take decisive data-driven action swiftly, and communicate that action with indisputable clarity.

As always, I welcome your feedback; please reach out @swannysec.

References and More Information

¹ https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov/

² https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

³ https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/5/19-0995-f1

For more on Coronavirus risk from a business perspective: